The Arab-American Experience

— BRAVE CONVERSATIONS SERIES —

A Deliberate Approach to Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion

Lawrence Hall’s DEI Committee strives to ensure Lawrence Hall is a diverse, equitable environment of belonging and inclusivity. Having “brave conversations” about diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) in the workplace is a necessity for healthy company culture and requires honesty, compassion, and self-reflection of all involved. Our Brave Conversations Series highlights topics not normally discussed but that have deep, personal impacts on our staff, youth, families, and communities.

April is Arab American Heritage Month, so this month’s Brave Conversations will focus on issues facing Arab Americans today. Our next conversation is around the Arab American Experience.

Who are Arab Americans?

The Arab culture is one of the oldest on Earth. Arab Americans are U.S. citizens and permanent residents who trace their ancestry to, or who emigrated from, Arabic-speaking places in southwestern Asia and northern Africa, a region known as the Middle East. Not all people in this region are Arabs. Most Arab Americans were born in the United States.

Arab Americans have ancestry in one of the world’s 22 Arab nations, which are located from northern Africa through western Asia. The people of these nations are ethnically, politically, and religiously diverse but share a common cultural and linguistic heritage. The world’s 22 Arab nations are Algeria, Bahrain, the Comoro Islands, Djibouti, Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Kuwait, Libya, Morocco, Mauritania, Oman, Palestine, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Somalia, Sudan, Syria, Tunisia, the United Arab Emirates, Lebanon, and Yemen.

In the U.S., many people conflate “Arab” and “Middle Eastern,” but linguistic and geographical factors mean that these terms are not fully interchangeable, according to the Arab American National Museum (AANM). The Middle East includes non-Arabic nations such as Iran, Israel, and Turkey. Similarly, not all Arabic nations are located in, what is considered the Middle East including Egypt, Algeria, and Morocco. A common misconception is that all Arab Americans are Muslim. Approximately 25 percent practice Islam, and an estimated 63 to 77 percent are Christian, according to the Arab American Institute.

Since September 11, 2001 some of the United States’ most aggressive racial profiling practices have come in the immigration context under the thinly veiled excuse of preventive law enforcement. The United States government has developed immigration law and law enforcement policy that by design or effect applies almost exclusively to Arabs, Muslims, and South Asians. Post-September 11 backlash has significantly spilled into the employment arena.

Workplace challenges

Harassment of Arab Americans at work apparently became an act of patriotism for some of their coworkers following September 11. The types of comments and epithets became increasingly more threatening and intimidating with more terrorist references, and linking anyone from any country in the Middle East to terrorists and suicide bombers. According to the EEOC, from September 11, 2001, to February 11, 2004, 904 charges were filed alleging post- September 11 backlash discrimination. The charges in this category include national origin discrimination claims by an individual who is or is perceived to be Muslim, Arab, Afghan, Middle Eastern or South Asian, or individuals alleging retaliation related to the terror events. The primary claims were “wrongful discharge” and “harassment.” In addition, Arab Americans were also not hired and denied promotions because of their national origin. The harassment included offensive slurs, e.g. “sand n—,” “camel jockey,” “terrorist,” “suicide bomber,” and “political“ comments such as “we should turn the Middle East into a parking lot.”

Claims of workplace religious discrimination against Muslim women who wear the traditional headscarf continues to increase throughout the United States. Hani Khan, a 19-year-old San Mateo, California Muslim woman who allegedly lost her job at Hollister Co. for refusing to take off her hijab at work, filed suit in the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California against the clothing store’s parent company, Abercrombie & Fitch. Khan was employed there for four months and was at first told her headscarf was acceptable as long as she wore company colors. But after a district manager and corporate human resources manager asked that she no longer wear it, Khan refused and was suspended, then terminated. Khan said when she was told to remove her scarf after being hired with it on she felt “demoralized.” She said growing up in the United States where “the Bill of Rights guarantees freedom of religion,” she felt “let down.”

What can you do?

- BE VOCAL: Be an example of an ally, when you see discriminatory practices call it out, educate, and refuse to condone that behavior. Speak up against discriminatory legislation.

- BE EMPATHIC: There needs to be greater awareness and recognition that the individual rights of all are at risk when one community is target and not only those of that community.

- BE HONEST: Post-September 11 led to many people being misinformed about Arab Americans, and many still hold that information to be true. Be honest with yourself and allow yourself to be properly educated.

- BE INFORMED: Learning factual information about Islam and Muslims, Arab Americans, and any community you have little knowledge about, can lead to understanding and acceptance. Ignorance is the most prevalent weakness a person can overcome.

RESOURCES

The Dangerous Bullying of Ilhan Omar

Supporting Arab American Students in the Classroom

MOVIES

Amreeka (2009) — directed by Cherien Dabis

American Arab (2013) — directed by Usama Alshaibi

A Thousand and One Journeys: The Arab-Americans (2016) — directed by Abe Kasbo

Reel Bad Arabs: How Hollywood Vilifies a People (2006) — directed by Sut Jhally

Axis of Evil Comedy Tour (2005) — directed by Michael Simon

TV SERIES

The Secret of the Nile (Netflix)

Justice (Netflix)

Ramy (Hulu)

BOOKS

Never in a Hurry

Naomi Shihab Nye

Out of Place

Edward Said

The Girl in the Tangerine Scarf

Mohja Kahf

Arab in America

Toufic El Rassi

Under My Hijab (Children’s book)

Hena Khan

Amina’s Voice (Children’s book)

Hena Khan

MUSIC

Arab Americans in Popular Music

PODCASTS

The Arab American Experience — SMG Sound Network

From Cairo to Brooklyn: The Arab American Experience — Noran Morsi

Search

Categories

- Blog (17)

- Grants and Awards (5)

- News (77)

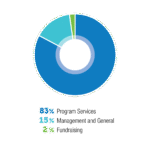

Lawrence Hall is a 501(c)(3) organization. Gifts are deductible to the full extent allowable under IRS regulations.

©2025 Lawrence Hall All rights reserved. Site Construction by WorkSite